|

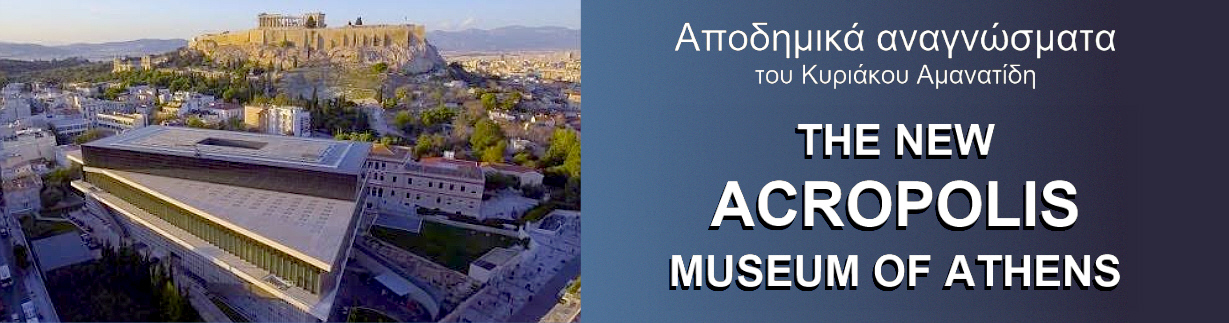

THE

NEW ACROPOLIS MUSEUM OF ATHENS

On Saturday June 20, 2009, the New Acropolis Museum of Athens opened its

doors to the public for the first time.

Τhe new Acropolis

Museum has a total area of 25,000 square

metres, with exhibition space of over

14,000 square metres, ten times more than

that of the old Museum on the Acropolis,

built in 1874. This is a new Museum, with

all the amenities expected in a Museum of

the 21st century.

The

Museum was officially inaugurated during a

nationally televised ceremony that brought

together Greece’s political leadership

and scores of international dignitaries.

Professor

Dimitris Pantermalis, the Director of the

new state-of-the-art facility, pointed to

numerous mutilated sculptures on display

in the third-storey Parthenon Gallery,

sculptures the other half of which is

found at the British Museum in London.

Instead, white-coloured plaster replicas

depict the missing friezes in the New

Acropolis Museum most celebrated gallery.

The

President of Greece, Mr Karolos Papoulias,

also made mention of the missing Parthenon

Marbles, when he said:

“Today,

the whole world can see, all together, the

most significant sculptures of the

Parthenon. Some are missing. Now is the

time to heal the monument’s wounds with

the return of the marbles to where they

belong … their natural setting”.

The

Prime Minister of Greece, Mr Costas

Karamanlis, stressed the cultural aspect

of the Museum, and the fact that it forms

part of the world’s cultural heritage:

“In the

sacred hill of the Acropolis the world

views the forms that ecumenical and

eternal ideals take. In the New Acropolis

Museum the world can now ascertain these

forms, these ideals, reuniting them and

allowing them to regain their radiance …

Welcome to a Greece of civilisation and

history; together we are inaugurating a

Museum for the supreme monument of the

Classical civilisation: the Acropolis

Museum”…

“The

Acropolis Museum is a reality for all

Greeks; for all the people of the world.

It is a modern monument, open, luminous

and is harmoniously intertwined with

Parthenon itself. It permits the Attica

sun to shed its light on the ancient works

of culture and allows the visitor to enjoy

and appreciate the details of the

exhibits. This modern monument narrates

the history of democracy, art, rituals and

everyday life”.

The opening of the New Acropolis

Museum, coming five years after the

successful running of the Olympic Games of

2004, constitutes a bold statement from

Greece that she reclaims her historical

and cultural heritage.

It also serves as a stern notice

to Britain that the Parthenon Marbles

belong in the New Museum, next to the

Acropolis, from which they were taken by

the Scottish aristocrat Thomas Bruce,

seventh earl of Elgin, more than 200

hundred years ago, and now housed in the

London’s British Museum.

The

Athens Acropolis Museum is one of the

finest buildings in the city of Athens,

and one of the most functional Museums in

the world. It was designed by the

Swiss-born,

New York-based architect Bernard Tschumi,

in collaboration with the Greek architect

Michael Photiadis.

The Museum is designed in such a way as to make the most of natural light,

and it incorporates seismic technology, so

as to survive

earthquakes measuring up to 10.0 on the

Richter scale,

in anticipation of the region’s frequent

earthquakes.

The New Acropolis Museum was

scheduled to be completed in time for the

Athens Olympic Games in 2004. However,

during excavation a series of

archaeological discoveries were made at

the site of Makrigiannis – which

consisted of artifacts such as marble

busts, mosaic flooring, and amphorae.

Assessment of these objects, and changes

to the plans so as to accommodate them,

led to delays in the completion of the

Museum.

The

base of the Museum contains an entrance

lobby overlooking the Makrygianni

excavations, as well as temporary

exhibition spaces, retail and all support

facilities. A wide ramp leads up to the

first floor. Transparent sections in the

ramp's floor allow visitors to see the

exposed archaeological remains below that

were found during the preparation of the

site.

The structure of the Museum

actually sits above on-going archeological

excavations. In the process of digging the

foundation, a variety of artifacts was

discovered. This necessitated alterations

to the original design, so as to include

pylons to suspend the Museum over the

archeological site.

Along

the sides of the ramp, and as

free-standing installations, there will be

artifacts recovered from the Sanctuary of

the Nymphs, the Sanctuary of Asklepeios

and elsewhere on the slopes of the

Acropolis. The middle is a large,

double-height trapezoidal plate that

accommodates all galleries from the

Archaic period to the Roman Empire. There

will be a multimedia auditorium and a

mezzanine bar and restaurant with view on

the Acropolis.

Among the museum’s many

treasures are artifacts from the Archaic,

Classical, and Roman periods. All were

found in the Parthenon, on the slopes of

the Acropolis, or in other places adjacent

to Acropolis.

Amongst the best known sculptures are Caryatids,

five

female statues that supported a porch on

the Erechtheum temple on the Acropolis. An

empty space has been left for the sixth,

which is in the London British Museum,

amongst

portions

of the Parthenon frieze and other

sculptures, removed from the Acropolis by

Elgin at the beginning of the 19th

century. This collection is known as the

Parthenon marbles.

It should be mentioned here that

the design

includes a rectangular glass gallery that

will display the Parthenon marbles when,

not if, they are returned from the London

British Museum, to be repatriated to the

place where they were created and saw the

light of day, and to which they naturally,

culturally and artistically belong.

The collections of the Museum

are exhibited on three levels. A fourth

middle level is reserved for the auxiliary

spaces, which include the Museum shop, the

café and the offices. The Museum also

provides an amphitheatre, and a hall for

periodic exhibitions.

On the first level of the Museum there are the findings of the slopes of the

Acropolis, the

Archaic

gallery.

The design of the rectangular hall, with

its sloping floor, is a representation of

the ascension to the rock of Acropolis.

Another floor houses the

artifacts and sculptures from various

Acropolis buildings other than the

Partenon, such as the Erechtheum, the

Temple of Athena Nike and the Propylaea,

and findings from Roman and early

Christian Athens.

The last level, known as the

Parthenon hall, has the same orientation

with the temple on the Acropolis, and the

use of glass, which allows natural light

to enter, creates the illusion that the

Parthenon exhibits are viewed in their

natural setting.

Only about half of the original friezes, the metopes and the exquisite

pediments of the Parthenon, which

represent the acme of classical Greek art,

are on display, under the natural light,

but in a controlled

atmosphere environment. The other

half languish in the London British

Museum, deprived of their natural, and

native, surroundings.

In

their place the Acropolis Museum has

placed, temporarily, one would hope, the

plaster cast replicas – sold to Greece

in the 1840s by the British Museum.

Safekeeping of the exhibits is

ensured, as the Museum encompasses the

latest security technology.

The Museum is located in the

southeastern slope of the Acropolis hill,

some 300 metres from the top of the

“sacred rock”, as it was known in

classical times.

The entrance to the building is

on Dionysiou Areopagitou Street and

directly adjacent to the Acropolis

Station, line 2 of the Athens Metro.

The Rationale for returning to

the New Acropolis Museum the Elgin Marbles

The Museum marks the city’s

most ambitious attempt to date to reclaim

its cultural patrimony. In addition to

archaeological finds spanning 2,500 years,

Greece hopes the New Acropolis Museum will

one day house the Elgin Marbles, which the

Greek government has been trying to

recover from the British Museum since the

mid-1800s.

The

Elgin Marbles, also known as the Parthenon

Marbles, are a collection of classical

Greek marble sculptures, inscriptions and

architectural members that originally were

part of the Parthenon and other buildings

on the Acropolis of Athens.

The issue of the Elgin Marbles

has been the subject of dispute for some

200 years, with no tangible results. The

issue was revived in the early 1980s by

the then Greek Minister of Culture Melina

Mercouri, who began to make emotive

appeals for the return of the Marbles to

Athens.

Thomas

Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, was the British

Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in

Constantinople from 1799–1803. In 1801

he had obtained permission from the Sultan

to remove pieces from the Acropolis. From

1801 to 1812 agents removed on Elgin’s

behalf about half of the surviving

sculptures of the Parthenon, as well as

architectural items and sculptures from

the Propylaea and Erechtheum.

Greece

was then under the control of the Ottoman

Empire. For a small fee, Thomas Bruce,

otherwise known as Lord Elgin, was allowed

to basically take whatever he wanted, and

so he proceeded to loot much of the

Acropolis, including friezes and metopes

that were integral part of the Parthenon.

The

Marbles were transported by sea to

Britain. In 1816 the Marbles were

purchased by the British Government for

the sum of £35,000, and were placed on

display in the London British Museum. The

legality of the removal has been

questioned and the debate continues as to

whether the Marbles should remain in the

British Museum or be returned to Athens.

Proponents of the request for

the return of the Marbles claim that they

should be returned to Athens on moral,

historical and artistic grounds.

The main stated aim of the Greek

campaign is to reunite the Parthenon

sculptures around the world in order to

restore organic elements which at present

remain without cohesion, homogeneity and

historicity of the monument to which they

belong and allow visitors to better

appreciate them as a whole.

Presenting all the extant

Parthenon Marbles in their original

historical and cultural environment would

permit their fuller understanding and

interpretation.

Returning the Elgin Marbles

would not set a precedent for other

restitution claims, because of the

distinctively universal value of the

Parthenon.

Safekeeping of the marbles would

be ensured at the New Acropolis Museum,

situated to the south of the Acropolis

hill. It was built to hold the Parthenon

sculptures in natural sunlight that

characterises the Athenian climate,

arranged in the same way as they would

have been on the Parthenon.

The

Greek government has frequently requested

the return of the marbles, but the British

Museum, claiming among other reasons that

it has saved the Marbles from certain

damage and deterioration, has not acceded

to the request, and the issue remains

unresolved.

Lord

Byron condemned the removal of the Marbles

George

Gordon Byron was born on the 22nd

of January 1788 in London and died on the

19th of April 1824 in Mesologgi

in Greece.

He

was the best known Philhellene, and

visited Greece twice, during 1809-1811 and

1823-1824. In his first visit he toured

the Acropolis, and was appalled at the

damage caused to the Parthenon by Elgin,

when under his instructions the Parthenon

Marbles had been removed.

In

1812 he wrote the poem, “The Curse of

Minerva” – Minerva being the Latin

equivalent to goddess Athena, to denounce

Elgin's actions.

The

poem was written at the Capuchin Convent,

Athens, on 17 March 1811, and it consists

of 312 verses. The following 12 verses are

part of that poem.

And

last of all, amidst the gaping crew,

Some

calm spectator, as he takes his view,

In

silent indignation mix’d with grief,

Admires

the plunder, but abhors the thief.

Oh,

loath’d in life, nor pardon’d in the

dust,

May

hate pursue his sacrilegious lust!

Link’d

with the fool that fired the Ephesian

dome,

Shall

vengeance follow far beyond the tomb,

And

Eratostratus and Elgin shine

In

many a branding page and burning line;

Alike

reserved for aye to stand accursed,

Perchance

the second blacker than the first.

Lord Byron took up the subject

of the Parthenon Marbles again in 1812, in

the lengthy narrative poem “Childe

Harold's Pilgrimage”. Canto XI to XV of

'Childe Harold's Pilgrimage' are a tribute

to the Parthenon Marbles, and condemnation

for their removal from their ancestral

land. The following verses are from Canto

XV.

Cold is the heart, fair Greece,

that looks on thee,

Nor feels as lovers o’er the

dust they loved;

Dull is the eye that will not

weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy

mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had

best behov’d

To guard those relics ne’er to

be restored.

Curst be the hour when their

isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom

gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking

Gods to northern climes abhorr’d!

This article was compiled by Kyriakos

Amanatides

|